What's the biggest number you can think of?

The idea of playing a game where you and a partner take turns at naming a number bigger than the last has always amused me. In reality, I think it would be deathly dull but it does raise the question of what, truly, is a big number?

One million!

One million and one!

...

It's clear that naming numbers explicitly like this will only take us so far.

One million is 1,000,000 and we can imagine that we keep adding zeros. 1,000,000,000 is a billion, 1,000,000,000 is a trillion (and still less than the US national debt).

So what can we do? We need better notation!

Notation

The number of atoms in the observable universe is roughly 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,0000,000,000,000,000. We can write this much more concisely as .

We keen keep applying this, e.g. , , and so on.

This is starting to look promising. Just the first term, , has so many digits that if we wrote the zeros on individual atoms it would use up all the matter in the universe.

But you might be saying to yourself "Aren't we going to run into the same problem as before though?". We're having to write out more exponents in these so-called power towers to reach larger and larger numbers. Is there something beyond exponentiation?

Indeed there is, and we can get there by considering the following sequence: addition, multiplication, exponentiation. What should come next?

## Tetration

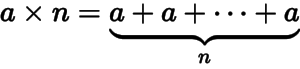

We can think of multiplying a number a by n as adding together n copies of a.

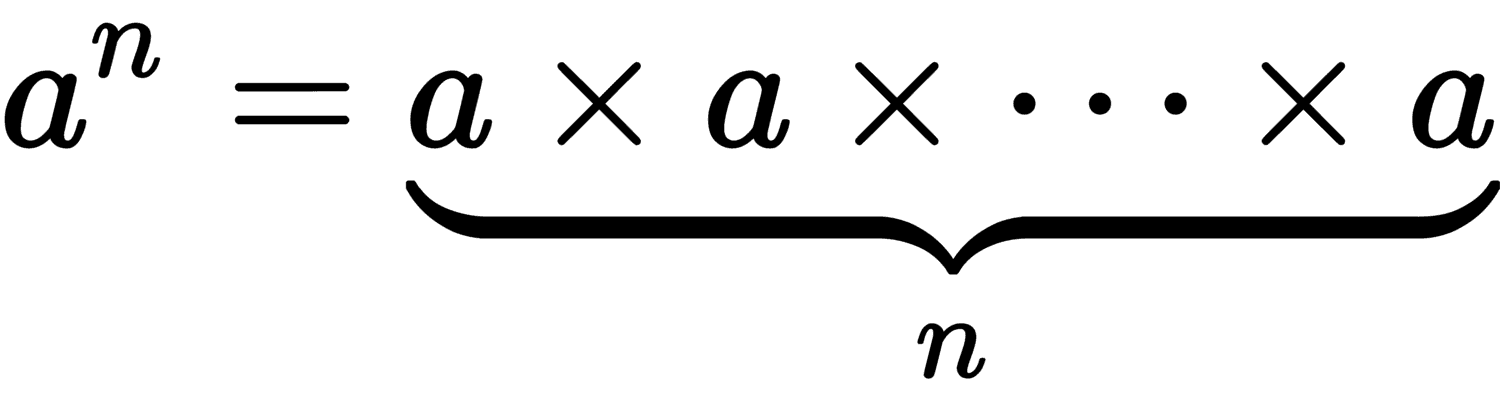

Likewise, we can think of raising a to the power of n as multiplying a together with itself n times.

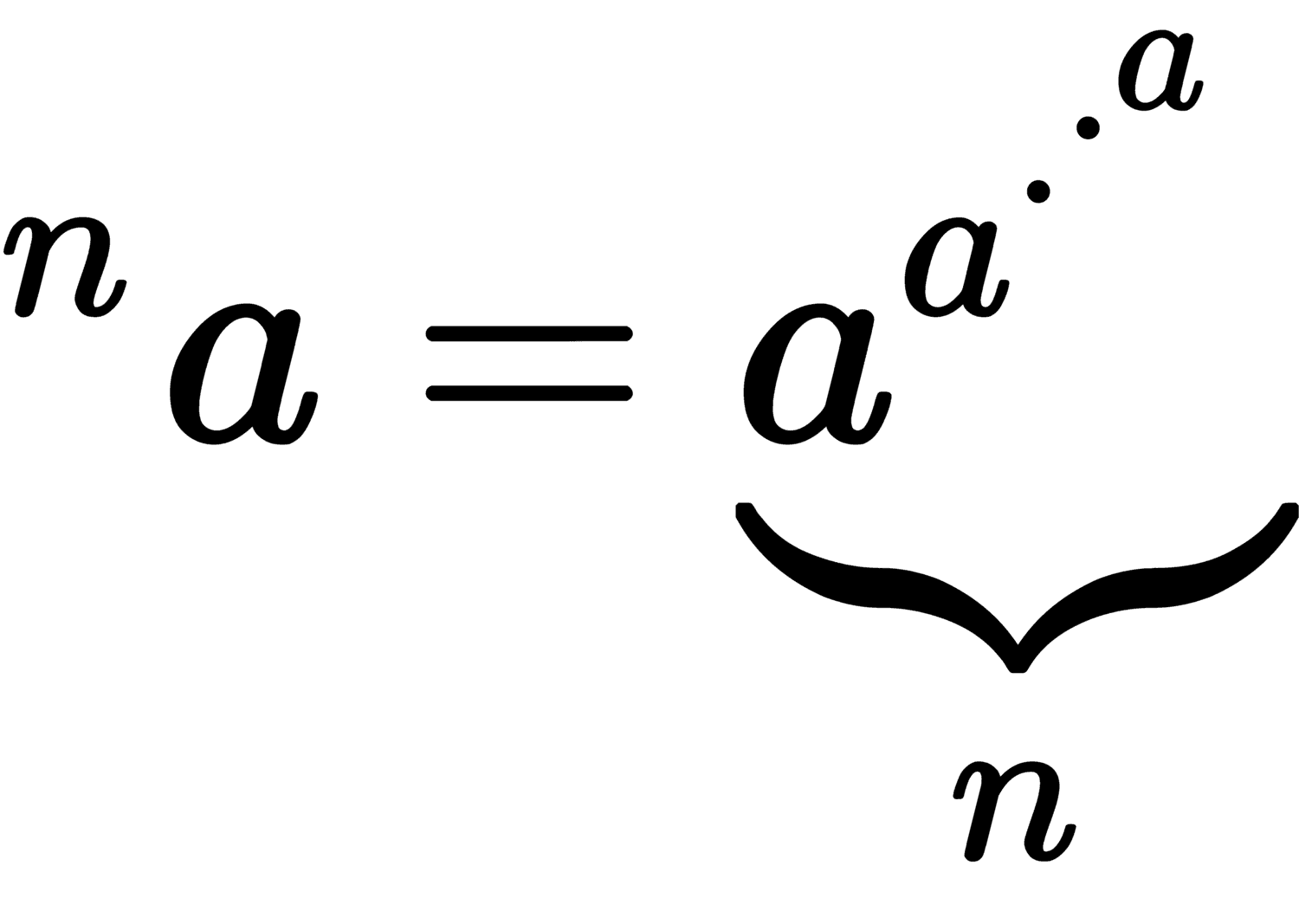

By analogy, tetration is the act of raising a to the power of a n times.

These are all examples of hyperoperations. The sequence continues forever, with the next few operations being pentation, hexation etc.

These names aren't very catchy, and it's a pain to write out long-hand what's going on. As you might have guessed, there's already a notation for that.

Knuth's Up-Arrow notation

Knuth's Up-Arrow notation is a method writing for very large numbers. It's closely related to the hyperoperations we just looked at (as well as something called Ackerman's Function which we'll come back to later).

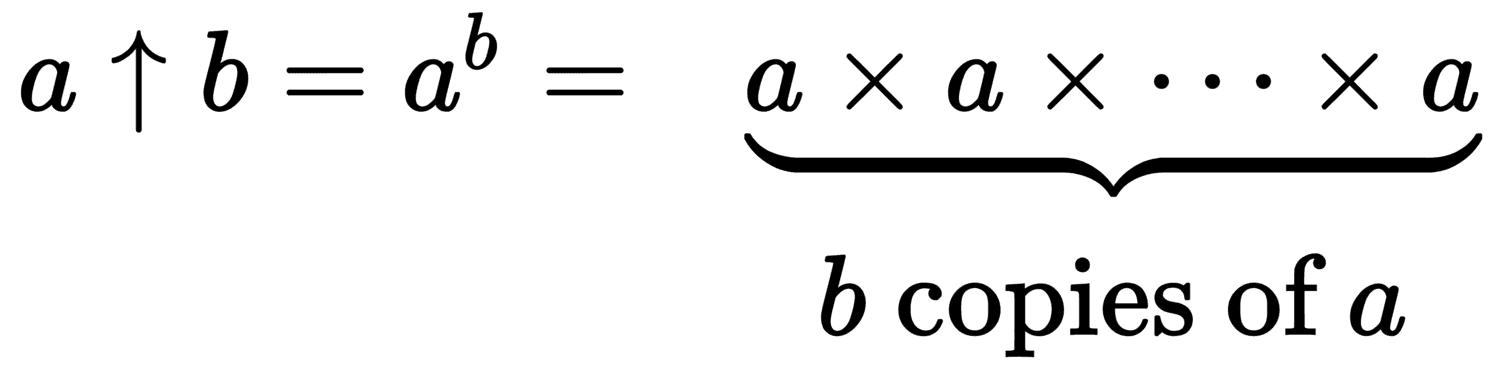

We can use a single up-arrow to represent exponentiation

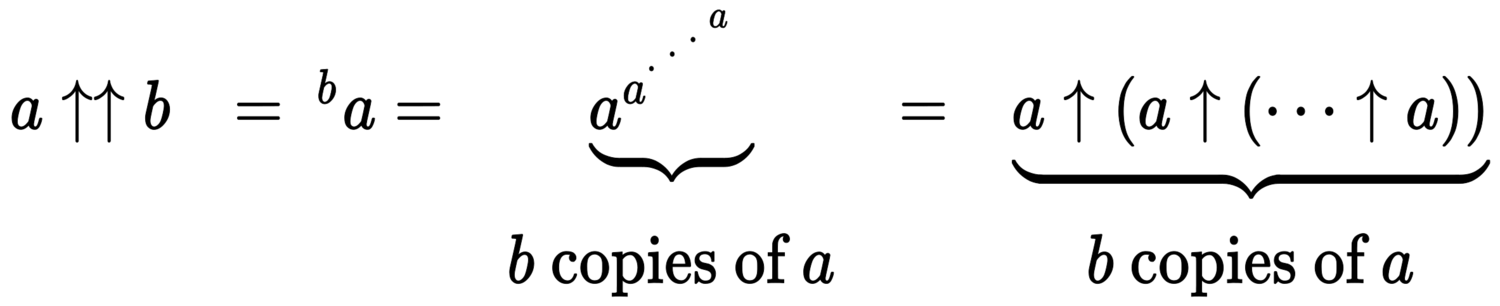

Two up-arrows give us tetration.

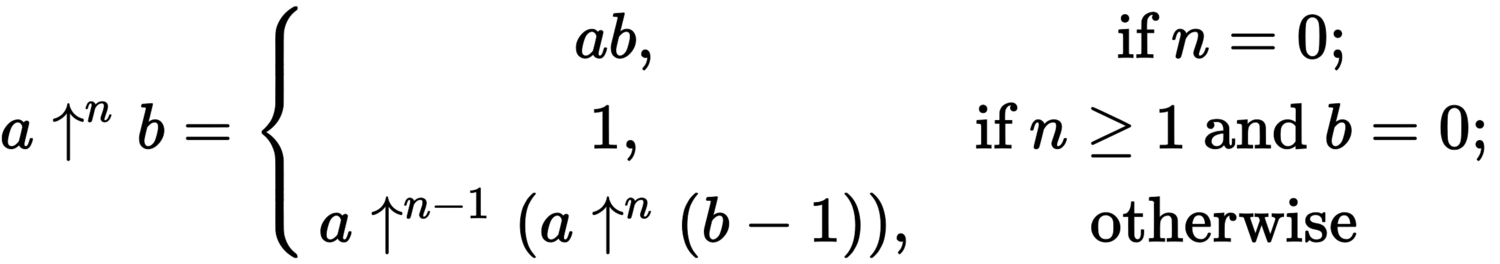

We can generalize and make this more concise using by using an index to represent how many arrows are present. This yields a nice recursive definition, i.e. we can define the 2 arrows in terms of 1 arrow, 3 in terms of 2, and so on.

Graham's Number

Let's take a quick break from learning about all this notation (it starts to get a bit samey) and use our new-found skills to define one of the most well-known examples of a big number. Graham's Number is an unimaginably large number which appears in the peculiar area of mathematics known as Ramsey theory.

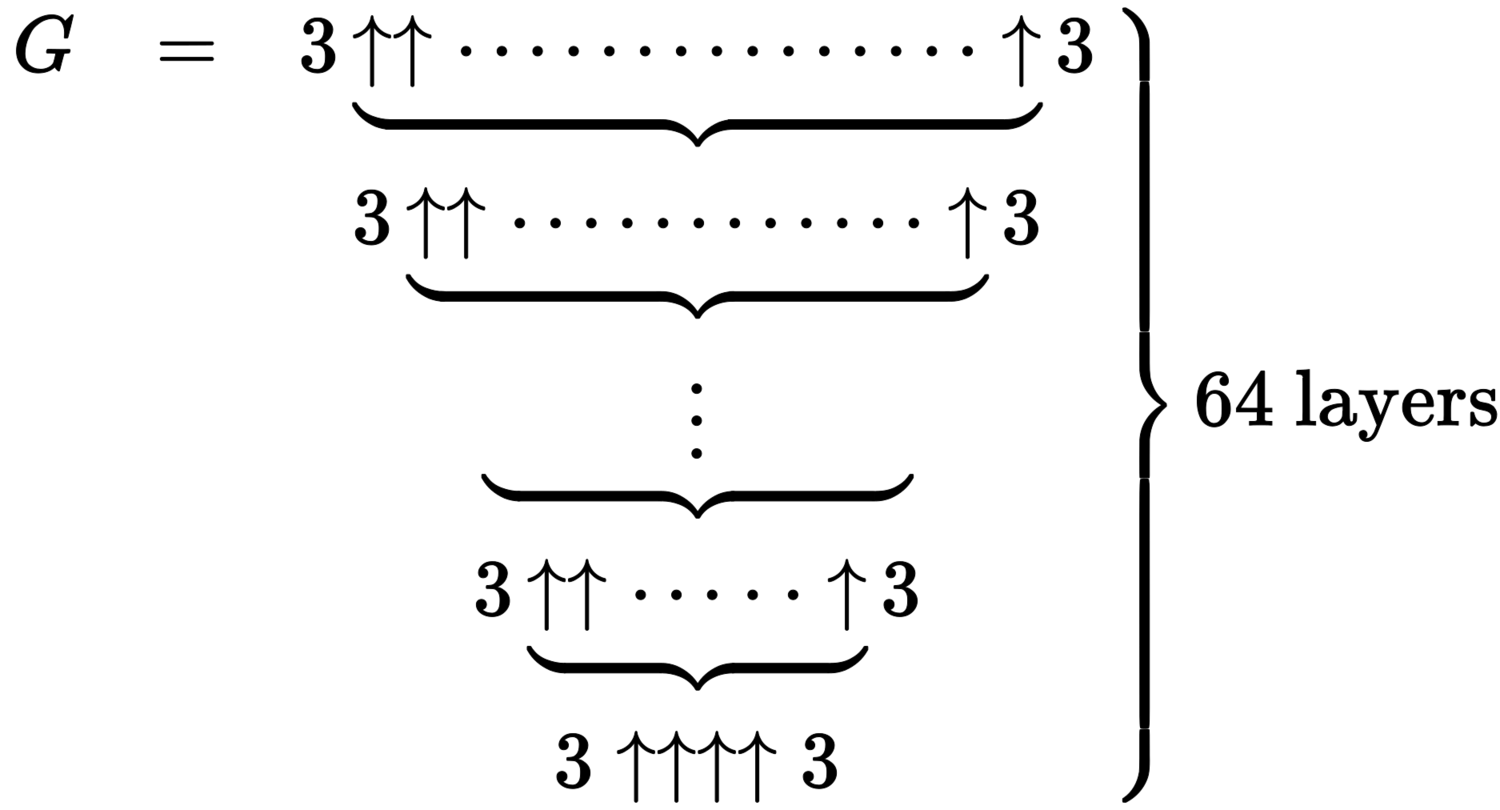

Using Knuth's Up-Arrow notation, we can define Graham's Number, G, as

where the number of arrows in each layer is given by the value of the layer below it.

I find just the process of defining the number mind-boggling, let alone the number itself! Graham's number came to prominence in 1977 when it was described as the largest number ever used in a serious mathematical proof.

The number actually appears as an upper bound for a particular quantity. Amusingly the best current lower bound is just 13. Makes Graham's number feel somewhat like overkill.

We've been looking at individual numbers and tools to write them down. Another fruitful approach is to consider some sequence or function which grows really, really fast...

## Ackerman's Function

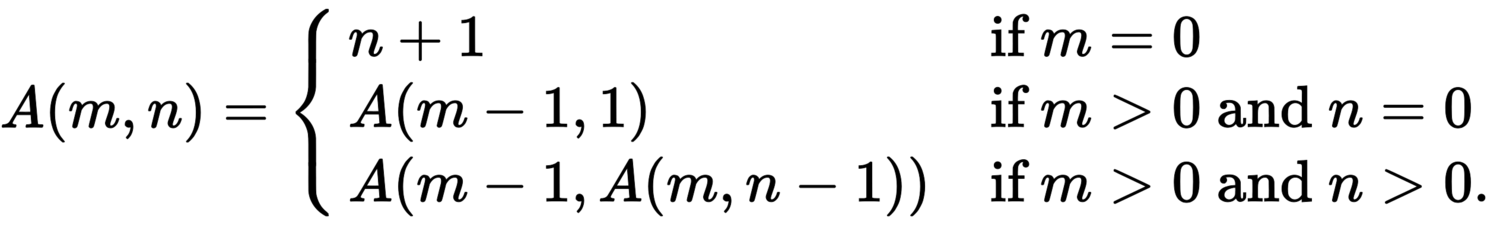

Ackerman's Function is just such a function. As a bonus, it has a simple definition

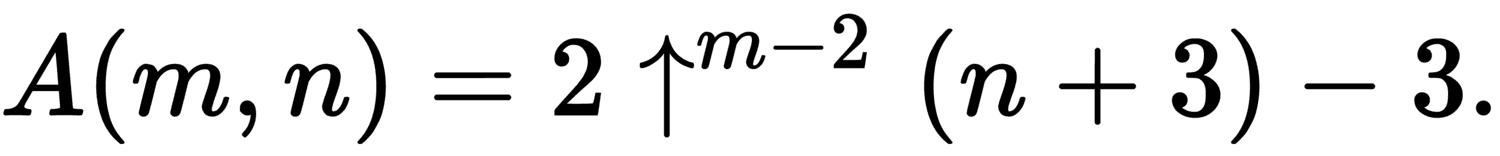

This function grows rapidly even for very small inputs. For example, A(4,2) is already an integer with 19,729 decimal digits. We can write the function in terms of the indexed form of Knuth's Up-Arrow notation we saw earlier on

We could stop here but what if I told you we could come up with a function that grows faster than any function you could possibly write down?

## Busy Beavers

This brings us to topic of the critter in the photo at the top of this post. The Busy Beaver function, like the Ackerman function, has a surprisingly simple definition. But before going into the details I want to highlight what I think is a most remarkable property. The Busy Beaver function is non-computable. There is no general algorithm to calculate the value of the function. In particular the Busy Beaver function grows faster than any computable function!

Now, this might sound a bit like cheating. Is it fair to deal with something that's non-computable? I say it is but first let's define what we're talking about.

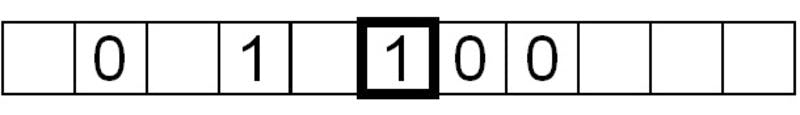

I'm afraid the definition is somewhat technical in nature. First up we need the concept of a Turing Machine. Such a machine is a very simple model of a computer. Notably in can simulate any computer algorithm. For our purposes you need to know that the machine can read and write from an infinitely long piece of tape (playing the same role as the memory in your computer). The tape is made up of squares, and these can be blank or have a one or zero printed on them.

The machine is very simple and can only read or write one square at a time and move left or right one square at a time.

We won't go into the details but we need one other piece of information which is the program that the machine will run. Without knowing exactly what it does we can always describe a program by how long it is. In the language of Turing Machines, we can talk about how many states the machine has.

Now we can give our definition. The Busy Beaver machine is the n-state Turing Machine which writes the most ones to its tape before stopping. The Busy Beaver number is the simply the number of ones this winning machine writes out.

With some hand-waving you might think of this as being asked to find the the computer program of a given length which generates the most output before stopping. If you've done any programming yourself, you'll notice that this gives you a lot of latitude in what you can do!

The numbers the function generates are well-defined (in the sense that they do have fixed values) and what's more we've actually worked out the values for n less than 5. It might sound odd that we can compute the output of a non-computable function (it certainly does to me). However, what we're stating is that there is no general algorithm. For these small values of n we can enumerate every possible machine and prove whether it halts or not. Hence Busy Beaver numbers are intimately tied up with the Halting Problem.

These are: 6, 21, 107. Underwhelming right?

We have some bounds on the next two terms. For n = 5 we know the number is >= 47,176,870, and for n = 6 we have >= .

These things take off like a rocket. Remember, they will outpace any algorithm you can write down. So, I will make my answer to "What's the biggest number I can think of?" to be the Busy Beaver number. The only downside is that we'll never know what it is!

And there I will stop.

If this is your sort of thing, then I encourage you to check out this article on big numbers from Scott Aaronson. If you want to go beyond finite number then Large Countable Ordinals from John Baez will be up your street.